Zarko Tankosic, Indiana University

[The paper presented at the 109th Annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America held at Chicago 3-6 January 2008].

As evident from the title, I present the preliminary results of the two years of field survey in the Karystian Kampos (or plain) located west of the modern town of Karystos in the southern portion of the island of Euboea, Greece. I say ‘preliminary’ because we are fresh off the field and the material has not even been cursorily studied by the team of specialists that Southern Euboea Exploration Project (or SEEP) has gathered to investigate and interpret the survey results. Nonetheless, some very tentative conclusions on the nature of use and occupation of this part of southern Euboea can be drawn from the present level of research. [SLIDE] Combined with other work already done in the area or currently under way, I hope that it will be possible to significantly add to our knowledge of antiquities and ancient habitation in this part of Greece. You will forgive me if I am today slightly biased towards the prehistoric section of the survey results since that section is of particular interest to me. [SLIDE]

The area in question is located west of the town of Karystos in the part of southern Euboea referred to as Karystia. [SLIDE] Karystia geographically consists of the horseshoe-shaped Bay of Karystos and two peninsulas bordering it: on the west there’s Paximadhi and on the east is the Bouros-Kastri region, as we call it, although, as far as I am aware this area as a whole does not have a specific or a universal name. Karystia is on the north bordered by the mountain ranges of Koukouvayia, Ochi, and Lykorema. The Kampos Plain is located northwest of the bay and stretches roughly east-west, starting at the head of the bay, where it is the broadest and where Karystos is located, and going towards Marmari on the western Euboean coast. It is the largest agriculturally viable piece of land in the area and is also fairly well watered, especially in the spring. This part of the island, separated from the rest of Euboea by high mountain ranges and from Attica by the southernmost part of the Euboean channel, which is much wider at this point than anywhere else between Euboea and the mainland, is quite different from the rest of the island in climate and vegetation. In fact, Karystia is, I think, best described as part of the Cycladic area rather than Euboea and the mainland of Greece, with which Euboea, being so close to it, is usually lumped together. A salient feature of the Karystia is Mount Ochi, which towers over the bay at the height of 1400masl. Another important feature that characterizes this region is the strong winds that blow here during most of the year, but particularly in midsummer, during the meltemi season. These winds not only influence the weather but also the sailing conditions and the mood of people who live or just happen to be in Karystia during their season.

[SLIDE] In case you were wondering why this chunk of Greece is archaeologically important, here are some reasons for you—aside from the very nice beaches that provide a wonderful incentive for fieldwork, Karystia forms a triangle with two other adjacent regions—the Cyclades and Attica. Material evidence shows that intensive contacts existed among these regions from prehistory. Thus Karystia, a place which by itself straddles the borderline between island and mainland, is ideal for examining some of the components of mainland – insular and inter-insular interaction. Some of the issues to which Karystia can contribute are the initial settling of the Aegean islands, the nature of prehistoric trade in Melian obsidian (especially in the light of results from our Kampos survey, as we shall see soon), prehistoric sea travel and maritime communication and interaction networks, and so on. Finally, southern Euboea, in combination with its adjacent regions is a suitable ground for examining some of the more elusive, but no less interesting, socioeconomic questions about prehistory identities and social structures and boundaries and how were they formed, maintained, and influenced by interaction.

[SLIDE] As you can see, the Kampos is positioned between the parts of Karystia that were previously surveyed by SEEP. Therefore, one of the reasons for undertaking this survey was to fill in the gap in the survey data from the area. The second reason for choosing the Kampos as the setting for our survey is that the Kampos is the largest agriculturally viable and fairly well watered stretch of land not only in southern Euboea but also among the northern Cycladic islands. We assumed that such piece of land would have been an important resource for people in antiquity. Thirdly, we wanted to test the extent and consequences of possible alluviation in the Kampos to archaeological sites in the area. Finally, one of our main goals was to test the reliability of the so-called ‘route-survey’ method employed in the survey of the eastern part of the peninsula.

The survey was carried out using different methodologies in the two seasons in the field. [SLIDE] The first fieldwork season, which lasted four weeks, was more of a pilot project executed with limited assets in order to get a better idea of the presence or absence of ancient remains in the survey area. The surveying team consisted of between two and four people walking in transects determined mainly by natural or man-made features of the terrain. The methodology intentionally corresponded to the ‘route survey’ of the eastern part of the Bay of Karystos. The transects followed paved and unpaved roads, footpaths, gullies, ravines and current or seasonal water flows. Moreover, two long arbitrary transects that coincided with the edges of the survey area were surveyed on the foothills on both the southern and northern edges of the Kampos. The team members were also allowed to depart from the transects and investigate any areas that seemed promising as potential location of findspots. Only a small representative sample of material was collected during this phase of the survey and only from locations that were designated as findspots.

During the second five-week-long season a different method was used. The survey team in the 2007 season consisted of seven to ten people in the field at any one time. [SLIDE] The entire survey area was divided into arbitrary 100X100m squares, which were then surveyed independently or in clusters using the stratified sampling approach. ‘Stratified sampling’ in this particular case means that the squares to be surveyed were not chosen randomly but with respect to specific predetermined rules; in this case the squares were selected in such a way as to include all the geomorphological features present in the survey area (e.g. southern foothills, northern foothills, central flat plain, proximity to the sea, ravines, gullies, water courses, roads, etc.) as well as take into account some of the results of the 2006 season (e.g. locations of discovered findspots or 2006 transects). [SLIDE] The 100X100m squares were further divided in ten 10m wide and 100m long transects, each surveyed by a team member under the assumption that surveyors are able to inspect an area that extends c. 5m on each side of them. Moreover, each transect was further subdivided into five 20m long sections, which served as the basic recording units in the field. Total, albeit unsystematic, collection was carried out on the surface of all the areas designated as findspots, while the thin material scatter in between the findspots was recorded (in case of non-feature material) or recorded and collected (feature sherds, obsidian, etc.). Naturally, sometimes we had to adjust certain aspects of this ideal methodology to accommodate the situation we encountered in the field; however, the discrepancy that that produced was not large and, for our purposes largely negligible.

Approximately 30% of the entire designated survey area was covered using the intensive methodology just described and perhaps another 5% of the area using the extensive methodology. [SLIDE] In the course of the two seasons in the field 36 findspots were discovered—20 in 2006 and the rest in 2007. A findspot was, in this case, very loosely defined as a restricted concentration of material, which is normally denser than the ‘normal’ off-site scatter or, as it is frequently known, ‘background noise’. Of the 36 findspots at least 15 are either purely prehistoric or have a prehistoric component among the material that can be dated to other periods as well. The material from 3 locations is tentatively identified as Classical or Hellenistic, 21 findspots are either Roman or have a Roman component, and the material found on the surface of 5 locations can be identified as belonging to the Byzantine era. There is only one findspots to which we could not assign a preliminary dating. Please, bear in mind that these dates are highly preliminary and many of them have been assigned while the material was still in the field. It is possible and in fact probable that there will be some corrections once the material is studied by specialists.

It appears that the off-site scatter of later (e.g. Roman and early Byzantine) material is on average denser in the vicinity of the main modern road that extends roughly east-west and connects Karystos with Marmari. This, in combination with several findspots of the same date located on both sides of the road, suggests that this route could have been used as one of the main east-west thoroughfares in antiquity. Besides this, the post-prehistoric sites of special interest include a [SLIDE] rustic sanctuary of Classical and/or Hellenistic date, [SLIDE] two small Byzantine chapels, one of which is quite well preserved, and [SLIDE] what appears to be a Roman pipe which could still be in situ. Of the findspots we could not date with any certainty the most intriguing is a group of cist-type graves [SLIDE] visible in the scarp created by a seasonal stream. No human or other types of remains were found in the vicinity of the graves so it was not possible for us to date them. This type of constructed cist grave was common in this part of Greece in several periods, starting with the FN. However, the lack of any grave goods combined with the fact that the material found in the vicinity was all of late Roman – early Byzantine date, suggests that the safest assumption, but only an assumption nonetheless, would be that these graves are dated to one of these periods.

The information we collected about prehistoric periods in the Kampos was, to say the least, somewhat unexpected [SLIDE]. First of all, we did not expect to find as many, or – to be honest – any, prehistoric findspots in the Kampos. Basing our expectations on the results from the 2006 season, where only one prehistoric findspot was located in the foothills north of the Kampos, and the fact that only one prehistoric site was known in the area from years of prior surveys nearby (the EBA Ay. Georgios), we thought that most or all of the prehistoric sites or other evidence in the Kampos must have been concealed by alluvium which has been accumulating in the area in post-prehistoric periods. The second unexpected thing was the nature of the prehistoric findspots we were able to locate. Most of the findspots in the Kampos that are dated to the prehistoric period consist almost exclusively of larger or smaller obsidian scatters. We have found pottery on the surface of only several of those findspots and even there the pottery was extremely fragmented and worn to the point where it is not identifiable. Some of the surface lithic scatters are quite large. For example [SLIDE], on findspot 07N35, located just west of the EBA site of Ay. Georgios, more than 2500 pieces of obsidian were collected from an area of about 150 by 100m in extent. [SLIDE] Another 300 pieces come from findspot 07S28. The amount of material from other such findspots in the Kampos is usually more modest, but still, the almost complete lack of pottery is somewhat confusing.

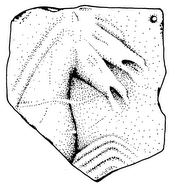

At the moment I am not able to give you the most reliable dating of the obsidian scatters from the Kampos since the material has not been properly studied. Nonetheless, it seems that most of those findspots can be at least tentatively dated to the EBA period or the FN/EBA transition. The material from the Kampos has two main characteristics—it consists almost entirely of obsidian, which is a characteristic of all the Neolithic and Bronze Age assemblages found in the area thus far, and, second, in some locations the almost complete reduction sequence (or chaîne opératoire) is present in the material, some parts of which you can see, I hope, on this slide. Inconclusive as these results may be at present, they are still informative. [SLIDE] First of all, it is evident from the material and its distribution that southern Euboea was an important center in the EBA obsidian trade in the Aegean. It is hard to say if Karystia was a consumption or redistribution center at this moment, but I believe it could have been the latter. Secondly, it seems that the extent of alluviation in the Kampos was much less detrimental to ancient sites than what was previously thought. This gives us hope that our results, although they represent only a sample, are not entirely biased. Furthermore, if we accept at least as a possibility that the alluviation was restricted and that it did not create as big a bias in our data from the Kampos, then Ay. Georgios was, indeed, the only large EBA settlement in the Karystian Plain. If this proves to be correct then it has implications for the sociopolitical relationship between EBA settlements in the region that have yet to be explored since it is feasible that Ay. Georgios was exercising some form of control of an important agricultural resource such as the Kampos.

To summarize [SLIDE], the results of the survey have shown that the Karystian Kampos was exploited or inhabited during the EB period and after that from Classical and Hellenistic times until the present. Material earlier than FN is missing from the part of Kampos we have surveyed, and we didn’t find any evidence that the area was used between the end of the EBA and the Classical period either. This is more or less similar to the situation in the rest of Karystia and, indeed, southern Euboea, where the earliest signs of human presence are dated to the FN. Moreover, there is no material evidence that belongs to the last phase of the EBA, that is EB3, or to the very end of the EB2 period or the so-called ‘Kastri/Lefkandi I phase’ characterized by the appearance of Anatolian-looking pottery. The only location that has yielded MBA material thus far in southern Euboea is Ay. Nikolaos in the village of Miloi, north of Karystos. The Kampos survey provided no new information on the MBA in the area. The LBA is almost completely absent from southern Euboea, which is a mystery too complicated to be addressed here. Although no Iron Age or Geometric material has been identified in the part of the Kampos included in our survey, a relatively large settlement from this period existed on and around the Plakari Hill just southeast of the Kampos at the edge of our survey area. Finally, Roman and particularly late Roman and early Byzantine times are extremely well represented in the material from the Kampos and the rest of Euboea, which is either a sign of increased population or of more intensive use of the plain. Material from those periods is also the one most commonly found off-site.

[SLIDE] Before I finish I would like to thank the wonderful team of volunteers who helped us survey this summer, the Institute for Aegean Prehistory for financially helping our work and the other individuals who either helped us with the field research or who have taken their time to read and comment upon this presentation.

Thank you.

Figure: The Kampos. Red: boundaries of the survey area; Blue: Transects surveyed in 2006; Yellow: Squares surveyed in 2007

Athens on MAVROMATAION (Μαυρομματαίων) STREET (marked in red on the map to your right). The street is located just a few blocks away from the National Archaeological Museum. The best way to get there is using the trolleys no. 3, 5, 11, or 13. These trolleys all go through the center and you need to get off one stop after the Museum, on the Patission (Πατησίων) Boulevard; Mavromateon is the street parallel to the one trolleys use, slightly up from where you exit, behind the School of Economics. An alternative way of getting there is to take the Green Line (also known as Line 1 or Elektriko) of the metro, in which case you need to get off at Viktoria (ΒΙΚΤΩΡΙΑ) station (see the map) traveling in the direction of Kifissia and walk two blocks up from the exit. Catching the bus there instead of at Ethniki Amina might be a better solution if you are already in Athens and/or have a lot of luggage. There are many KTEL buses leaving from Mavromateon Street and most of them are going to one of Attica's sea ports, so be sure you find the right Rafina bus (it is marked, see above). If you are already in Athens, you can also get a cab to take you to Mavromateon Street. The cabs inside Athens are cheap, but getting one is often a challenge.

Athens on MAVROMATAION (Μαυρομματαίων) STREET (marked in red on the map to your right). The street is located just a few blocks away from the National Archaeological Museum. The best way to get there is using the trolleys no. 3, 5, 11, or 13. These trolleys all go through the center and you need to get off one stop after the Museum, on the Patission (Πατησίων) Boulevard; Mavromateon is the street parallel to the one trolleys use, slightly up from where you exit, behind the School of Economics. An alternative way of getting there is to take the Green Line (also known as Line 1 or Elektriko) of the metro, in which case you need to get off at Viktoria (ΒΙΚΤΩΡΙΑ) station (see the map) traveling in the direction of Kifissia and walk two blocks up from the exit. Catching the bus there instead of at Ethniki Amina might be a better solution if you are already in Athens and/or have a lot of luggage. There are many KTEL buses leaving from Mavromateon Street and most of them are going to one of Attica's sea ports, so be sure you find the right Rafina bus (it is marked, see above). If you are already in Athens, you can also get a cab to take you to Mavromateon Street. The cabs inside Athens are cheap, but getting one is often a challenge.